Thank you for the invitation to join you today on unceded Ngunnawal and Ngambri country, presenting work prepared on the lands of the Wurundjeri people of the Eastern Kulin nations.

I gratefully acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been custodians of these lands for tens of thousands of years, and my own responsibility to care for Country

My role today is to convince you all that Australia can be a renewable energy superpower, and to advocate for the policy instruments that will see Australia achieve its superpower potential.

First, let me take a moment to place this work in context.

Climate change will do more damage to Australia than to any other developed nation.

It will have devastating effects on agriculture and aquaculture, and there will be more frequent and damaging bushfires and droughts that threaten biodiversity, the carbon stored in trees, people, and property.

And with over 90 per cent of the world’s economy now covered by net-zero commitments, international decarbonisation policies will also lead to an inevitable decline in Australia’s second and third most economically important exports: coal and gas.

But the same forces that threaten Australia’s economic prosperity are the same forces that create tremendous opportunities.

If we get policy setting right.

If we pivot to embrace new opportunities.

That’s because Australia has the best resources in the world for producing zero-carbon energy and goods.

Work by my colleagues, Ross, and Dr. Reuben Finighan, show that Australia can not only meet its own net-zero commitments. It can prosper, while contributing to a 6-9 percent reduction in global emissions. That is because Australia can be a large-scale exporter of zero-carbon products, including green metals and fuels, displacing carbon-intensive goods in the process.

This would not only be good for global carbon budgets, but for Australians.

Next week The Superpower Institute will release work that has quantified the potential mid-century benefits if Australia becomes a green export superpower, including revenues up to $987 billion per annum, with $386 billion from green iron

A strong economy – low unemployment, high incomes, and a strong budget – is not only essential for good public services. It is also essential for making the investments that can help us adapt to climate change.

Australia can prosper during the global decarbonisation process, because global production and consumption is underpinned by trade.

In a world with free trade, countries produce the goods in which they have a comparative advantage – the thing they do relatively better than anything else.

Australia’s comparative advantage is based on abundant resources for generating cheap renewable energy, together with reserves of conventional minerals including iron ore and bauxite. Australia also has generous reserves of transition minerals including copper, lithium, silicon, uranium, cobalt, nickel, graphite and the rare-earth elements. The IEA estimates that there will be a 7-fold increase in demand of these minerals in the first decade of global decarbonisation. Australia has swathes of non-agricultural land for growing renewable carbon, and human capital – with people who are experienced in research and development, mining, and agriculture.

When I raise Australia’s comparative advantage in renewable energy, people often point to other countries with abundant resources. For example, there is wonderful solar irradiation in China’s Gobi desert, and China has excellent wind resources in its north.

But physical supply is not the only determinant of price. It is also a question of whether those resources can be harnessed at low cost.

Cost can be pushed up if renewable energy displaces important agricultural production, or housing. It can be pushed up if the resources are thousands of kilometres from industrial and domestic centres, or if transmission needs to traverse difficult terrain.

But Australia is lucky. Large-scale renewable energy, used to produce green exports, would mainly locate in the north of Australia, in off-grid locations that do not compete with agricultural production or housing.

Price is also determined by demand.

There are broadly two types of demand for electricity.

The first is ‘domestic’ demand: the electricity that meets people’s day-to-day needs, in homes, hospitals, schools, and small business. We refer to this as ‘non-tradeable’ demand because large quantities can’t be displaced without relocating people. This demand can’t be traded away from a country.

Domestic, non-tradeable demand will increase dramatically as the world decarbonises. It will increase because a number of processes need to be electrified, including transport and domestic heating, and fuel for cooking. There will also be new sources of demand, like energy-intensive computation, and – for many countries, growth in population size, or growth in incomes.

This will create huge pressure on the price of renewables, particularly in countries with growing populations, or populations with growing incomes.

The second type of demand is ‘tradeable’ demand from industries that can be largely displaced by offshoring production – particularly demand created by energy-intensive industries, like iron and steel and aluminium.

Because domestic demand is a priority, in many countries domestic demand will push industrial users right up the supply cost-curve.

Zero-carbon electricity will become extremely expensive for energy-intensive industries.

It is the combination of these factors – abundant renewable resources, low competition for land, and low domestic demand – that mean that Australia could produce renewable energy that will be cheap by all international standards.

The reason that abundant, cheap renewable energy is so important to Australia’s industrial future and prosperity, is that the location of low-cost renewable energy will reshape international trade.

Current trade patterns are underpinned by fossil fuels, which are cheap and easy to move Transport is only 5 and 15 per cent of price, so fossil fuels can be sourced in one location and transported to another location for use in energy-intensive processes. The location of industry is strongly influenced by labour costs, and the cost of capital, rather than proximity to energy.

These trade patterns are badly distorted by the absence of an international price on carbon, which is one reason fossil fuels are so cheap.

But as the world decarbonises, industry will be powered with renewable energy, which is expensive to move. It requires transport with seabed cables, or conversion into hydrogen or ammonia. This means that energy-intensive production has a much stronger incentive to locate close to cheap, abundant zero-carbon electricity sources

This is why Australia has such wonderful economic opportunities in a decarbonising world. We have the potential to produce low-cost zero-carbon energy with our abundant resource, coupled with the fact that it is expensive to move zero-carbon energy.

The international market for steel provides an excellent example of how trade patterns will change as the world decarbonises.

Steel making is an extraordinarily carbon-intensive process, currently contributing 7-9 per cent of emissions from fossil fuels each year.

Steel-making has many steps, but the most carbon-intensive step is when iron ore is reduced into iron, using metallurgical, or coking coal, as the reductant. This step creates about 90 per cent of steel emissions, using blast-furnace technology.

The production and trade in steel is currently underpinned by cheap fossil fuels. Australia mines and exports iron ore, exports the metallurgical (‘coking’) coal which reduces iron ore into iron, and exports gas and thermal coal to power the process.

But that will change.

Australia will still mine iron ore. But because zero-carbon power is expensive to move, and because it is so energy-intensive to convert iron ore into iron, it will be cheaper to make iron in Australia, where renewable energy is abundant and cheap. This will make use of newer technologies, many of which use green hydrogen as a reductant.

Australia will have a comparative advantage in producing and exporting green iron, with less energy-intensive steelmaking processes completed overseas.

At the Superpower Institute we champion policies that remove barriers to private investments in green exports by addressing market failures, so Australia can capitalise on its comparative advantage.

We continue to advocate for a carbon price, in the form of a Carbon Solution Levy, and a carbon border adjustment mechanism that places the same carbon price on goods imported into Australia.

We believe that Australia’s carbon price should match the European Union’s Emissions trading scheme.

We support a Superpower Industry Innovation Scheme, for first-mover firms that create valuable knowledge and experience that benefits other green industrial producers, and

Government investments in common-user infrastructure, where private investors don’t have an incentive to invest efficiently. It is important to make these investments ahead of demand, so that missing infrastructure is not a barrier to green investments.

Such investments include electricity transmission to support ambitious investments in renewable energy, and infrastructure for the transport and storage of green hydrogen.

This suite of policies would work together to maintain a strong budget while establishing the foundations of a green superpower. A Carbon Solution Levy would provide valuable revenue to support the budget, investments in first-movers, and investments in green export infrastructure.

We also believe that an important role for government is to work with other governments to unlock demand for Australia’s green exports.

This work is essential: although the economic pressures of decarbonisation will eventually shift trade patterns, coordination and planning will be essential to create demand for green products in the earliest stages of the transition.

The Superpower Institute has strongly supported measures in the most recent Federal Budget, which uses ‘second-best’ policies to compensate for the absence of a global carbon price.

These policies are gathered under the umbrella of the Future Made in Australia policy’s net-zero transition stream, which is informed by the National Interest Framework that places a strong emphasis on industries where Australia has a comparative advantage.

Key policies include $2 per kilogram production tax credits to support green hydrogen, and investments in measurement of embedded emissions, so that Australia can participate in emerging green markets

The government is also consulting on policies to support green metals and fuels.

Turning to international policies, the Superpower Institute also welcomes the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, or CBAM, which represents the first green shoots of an international carbon price.

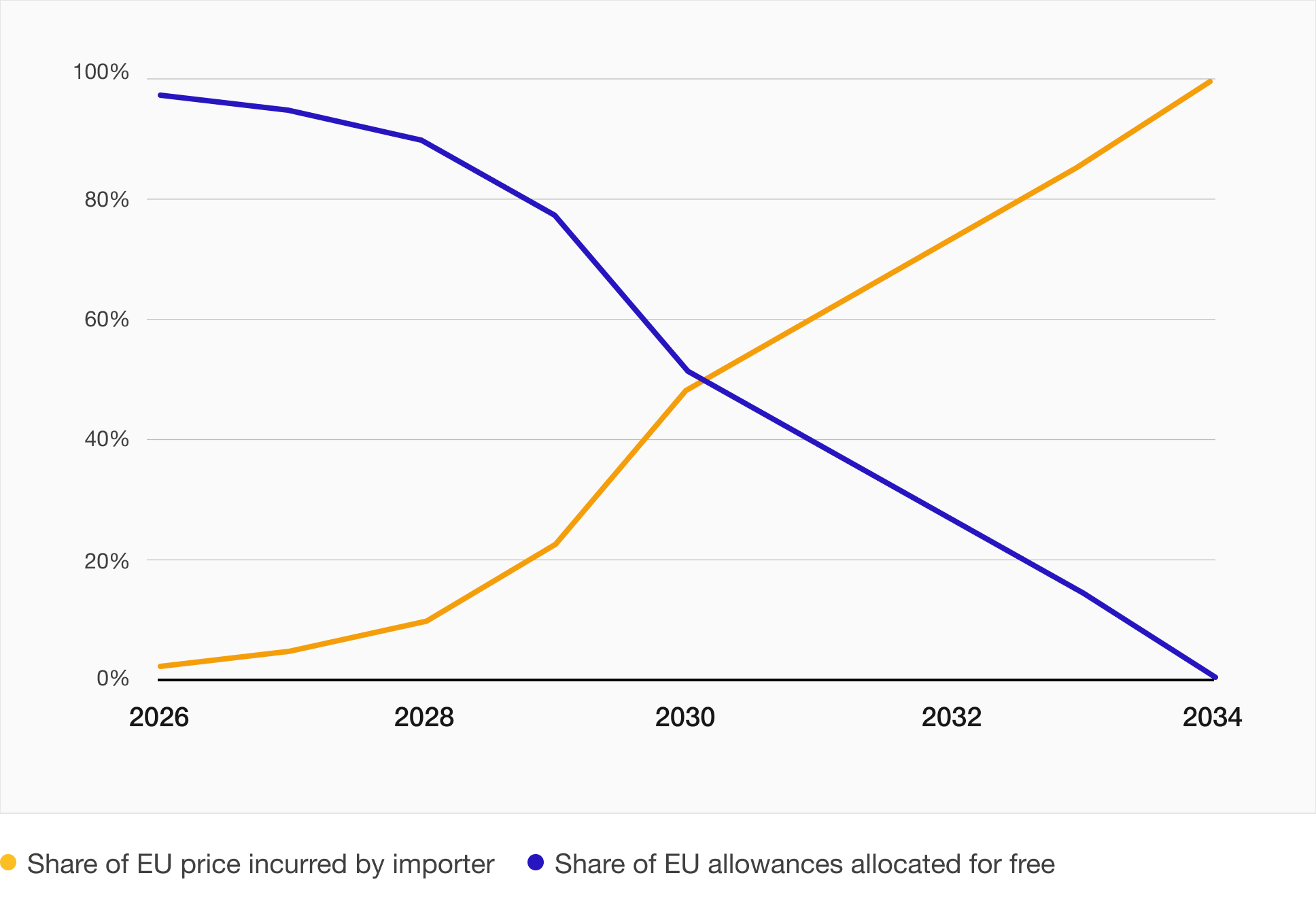

Introduced last year, the CBAM will progressively apply the EU ETS carbon price to particularly carbon-intensive imports, with the full price applied from 2034. Initially simple products are covered, including iron and steel, aluminium, cement, chemicals including fertilisers, hydrogen, and electricity

The EU plans to progressively expand the mechanism to cover more complex goods.

The CBAM avoids double-taxation: any price on carbon in the country of production is recognised, so it creates a new incentive for countries to introduce their own prices. And the CBAM will create a new international market for green goods – a market that will deepen and spread as other countries introduce similar measures.

The EU CBAM will drive early demand

And other countries will, in time, move to price the carbon embedded in imports.

That’s because CBAMs are essential for ensuring that domestic producers can compete on a level playing field with imports.

So where-ever there is a carbon price, there is an incentive to introduce border mechanisms.

While climate change policies in the US are now uncertain under a new administration, other countries are moving.

For example, China’s emissions trading scheme is now the largest in the world, and by the end of this year coverage will expand from the power sector to cover steel, aluminium, and cement. Prices in China’s ETS are low – averaging about $10 USD per tonne – but they are climbing rapidly, and recently peaked at about $20 USD.

This is how a global price on carbon will emerge: initially in a patchwork fashion, but inevitably.

These carbon prices will be good news for Australia, if we get the policy settings right, because they create an extraordinary opportunity for Australia to prosper while it contributes to the reduction of global emissions, by becoming a renewable energy superpower.

Ingrid Burfurd

Carbon Pricing and Policy Lead